NOTE - All text in this post is from bluegecko.org/kenya

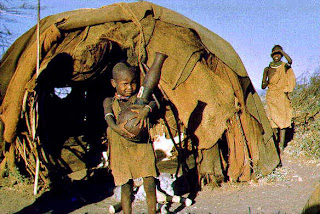

NOTE - All text in this post is from bluegecko.org/kenyaIn spite of the poverty of their land, the Turkana have managed to create something out of almost everything that surrounds them. The materials they use reveal an incredible ability to use almost everything that composes their environment: leather, iron from smelted haematite ore, copper from old electric wires, aluminum and tin from old cans and spoons, wood, beads and seeds, nuts, shells, fish vertebra, horns and hoofs, bones and stones, tusks, gourds, ligaments and plumes, hair and tails of livestock for decorations and charms, and nowadays even old car tires which are turned into supremely comfortable '5000-mile shoes'. To misquote the proverb: scarcity is the mother of invention!

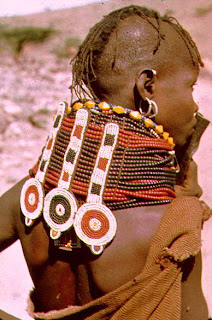

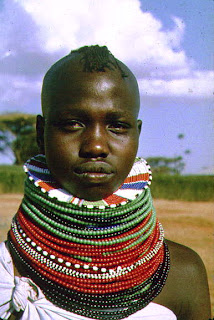

Like the Maasai and Samburu (and many other pastoralist peoples), they are also well known for their colorful and often intricate beadwork. This is primarily the preserve of the women, and their color, form and arrangement can have both social as well as ritual significance.

Such beautiful headdresses and sophisticated jewelry are common sights

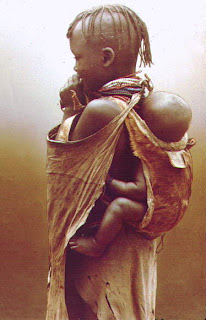

For women, marriage is the first and primary stage of adulthood. Turkana girls are usually married when between 15 and 20 years of age. They usually have some say in the selection of an appropriate husband. The wedding itself may take a couple of days and is perhaps the most important event in Turkana social life. There is much ceremony, dancing and feasting.

As mentioned elsewhere, a Turkana man can marry several women, so long as he is able to pay the bridewealth for each. And among the Turkana, this is hefty by any standards. As a young boy explained, "Turkana people can marry even 10 women so longer he is rich to avoid the dowry. 1 woman can cost 20 cows 30 goats and 15 camels and some donkeys."

Among Turkana women, a wife "generally considers it an economic advantage for her family to have additional co-wives since the women help each other in doing domestic chores and in caring for their animals. The co-wives may also help their husband find a new bride. They interview young women with a goal of finding one who will be compatible with them and hard working. Their husband usually must have their approval before going ahead with the wedding. For him, an additional wife also has disadvantages. The co-wives may get together, gang-up on him, and force him to do things that he does not want to do. More wives can mean more potential domestic trouble for a husband."

For the most part, pastoralism - the semi-nomadic herding of animals - is quite simply the only means of survival in such an arid location. Turkana rely almost entirely on cattle for their survival. It is an implacable logic that a man should aim to keep the largest herd of cattle possible, so that come the next drought, a comparatively large number of animals may survive. Grass has acquired an element of sacredness for its role in feeding cattle, and it is said that when a person wishes to make peace with his enemy, he will present him with a bundle of fresh grass. It is a powerful and symbolic offering which no-one can refuse.

The staple foodstuff in the Turkana diet is provided by a mixture of cow's milk and blood, though milk yield depends on the season, and may cease completely during prolonged dry spells. For these times, provision is made during the wet season by boiling fresh milk and letting it dry on skins, to make edodo powdered milk. In the dry season, the Turkana also eat fruit, most commonly wild berries which are either crushed to make dried meal, or mixed with blood and made into cakes.

Only rarely - either through extreme need, an animal's infirmity or old age, or for ritual purposes such as rain sacrifices, welcoming rites and mortuary rites - are cattle slaughtered; meat for eating is provided by goats and sheep instead (only in the dry season), which are also milked. The first animals to be slaughtered will have been specially chosen and castrated long before, as are sacrificial animals. These are presented to God with a simple and bluntly honest formula, something like "This is your animal, take it" or "This is your ox, take him." The sacrificers then continue: "Give us life, health, animals, grass, rain and all good things".

Apart from providing 80% of their food requirements, cattle have an amazing multiplicity of other uses, providing skins for clothing, mats, shelters, twine, sandals, slings, containers, bags and so on. The horns are used as containers (as they have been throughout the world), dung is burned for fuel, the hairs and tails are used as decorations and charms, the bones are turned into clubs, fat turned to oil for softening leather, stomach contents spread out for rituals...

On a more prosaic level, cattle are offered as gifts on social occasions, while fines and compensations suggested by elders for transgressions such as fathering illegitimate children are also expressed in head. Cattle can also be bartered for grain, tobacco, beads and ironware.

In the same way that elders are respected in part for their having survived, so a man with large numbers of cattle will be admired and respected, too, for the survival of his family and relatives rests assured. This is especially true given the scarcity of water and pasturage (which runs as a constant theme throughout Turkana life), which has itself raised the practice of livestock raiding (and the resulting warfare) to a quasi-economic pursuit, through which men are can acquire reputations for bravery as well as sudden wealth.

This is not just a matter of pride. The symbolic bridewealth payment, which of course is made in cattle, is traditionally very high, providing young men with a powerful incentive to establish their reputations and herds through raids on non-Turkana groups. The symbolic transfer of cattle thus not only compensates the bride's family for the expense of having raised her, but also signals the man's ability to found a successful and prosperous family for his wife and future children.

2 comments:

Turkana was such a great experience Deb!! If we do it again,lets get off the bus seemingly in the middle of nowhere,like that young Turkana guy that hitched a lift with us at night on our way back from kakuma...maybe we'll get lucky and find an accomodating home in a little village willing to put up a couple of strays for the night! wouldn't that be something!!!

Could you please tell me who took the photos of the Turkana women wearing Obolio?

Post a Comment